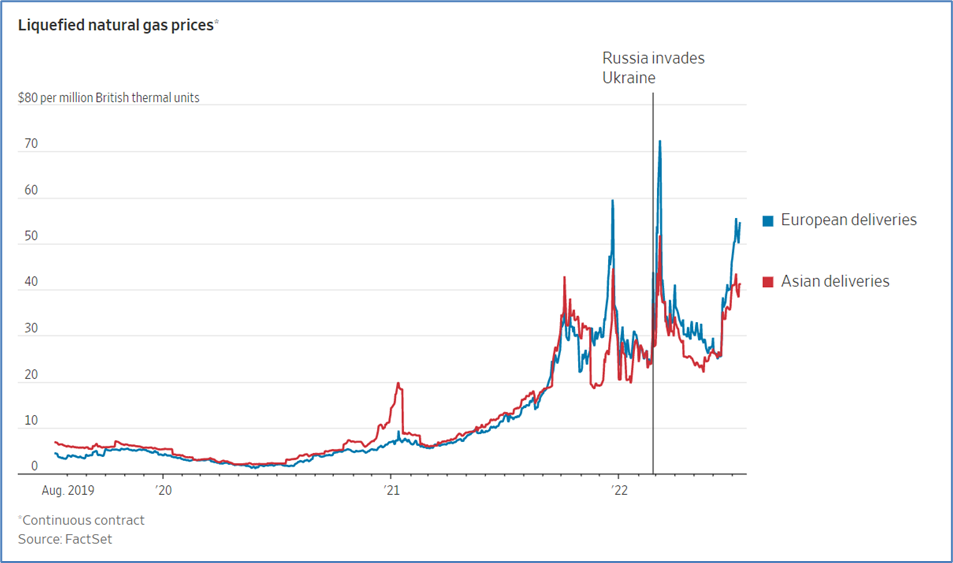

On behalf of the team at 5, I am pleased to forward our market letter for the second quarter of 2022. The dramatic increase in the price of electricity and natural gas noted in our Q1 letter continued its upward climb in Q2, fueled primarily by the war in Ukraine and its impact on the price of LNG. This dramatic increase is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Liquefied Natural Gas Prices from wsj.com

While Q2 was a boom time for sellers of LNG, it was a terrible quarter for those who support federal efforts to reduce carbon emissions. The United States Supreme Court significantly cut back the EPA's ability to regulate power plant emissions, and Senator Manchin put a final nail in the coffin of federal climate change legislation. In this issue, we focus on the Supreme Court’s recent decision in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency (“WVA v. EPA”) and discuss how this decision impacts future efforts to regulate the energy market. For our clients, the most important takeaway from the Court’s decision is that climate change regulation will remain almost exclusively in the hands of the states.

West Virginia vs. Environmental Protection Agency

The Supreme Court issued its decision in WVA v. EPA on June 30, 2022. Without delving into the details of the various regulations at issue, the case reviewed a challenge to the EPA’s Clean Power Plan (CPP), a Federal effort to reduce carbon emissions from power plants introduced during the Obama administration. Citing broad authority to regulate hazardous emissions granted to it by the Clean Air Act[1], the EPA promulgated rules in the CPP that would have forced states to adjust their power generation mix. The CPP required states to reduce the portion of electricity generated by coal and increase the portion of generation sourced from natural gas and renewable generation. The CPP never went into effect due to court challenges and then changes made by the Trump administration’s EPA. Even so, since it was possible that a future EPA would assert the broad authority claimed under the Clean Air Act, the Supreme Court decided to hear a challenge to this authority brought by West Virginia and certain other states.

For the first time, the Court employed the “major questions” doctrine to determine whether the Clean Air Act gave the EPA authority to reshape the electricity grid as envisioned in the CPP[2]. The Court’s conservative majority found that EPA’s plan (under the defunct CPP) to force coal plants to “cease making power altogether” was a major question. Therefore, the Agency must point to “clear congressional authorization” that supports the Agency’s action. The majority did not find sufficient congressional authorization in the language of the Clean Air Act to support the generation shifting rules in the CPP. In her dissent, Justice Kagan argued that the majority’s major question analysis effectively appointed the Court instead of Congress or the relevant agency, as “the decisionmaker on climate policy.”

Implications of this Decision: Can the SEC Require Companies to Disclose Carbon Emissions?

The Supreme Court’s decision is likely to limit other agency actions focused on climate change. If the Court decides that an agency action that addresses climate change is a major question (it is “highly consequential” or poses questions of “economic and political significance”), it is unlikely that the agency can take such action without very clear authorization from Congress. In our Q1 letter, we discussed the SEC’s climate change regulations, issued in March 2022. These regulations require all public companies to report on Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions in calendar year 2023 (and in some cases, Scope 3 emissions as well).[3] The SEC relied on a broad delegation of power under the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 to “promulgate disclosure requirements that are ‘necessary or appropriate in the public interest or for the protection of investors.’” We expect that opponents of these rules will challenge them using the Supreme Court’s new “major question” doctrine. If a Court reviewing the SEC’s rules determines that this new reporting requirement is a major question, the SEC will be hard pressed to uphold the new regulations. Neither the 1933 Act nor the 1934 Act spells out any authority for the SEC to address climate change.

Other Implications of WVA v. EPA: Biden’s Climate Options Limited

The Biden administration aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50% from 2005 levels by 2030. After the decision in West Virginia v. EPA, it will be difficult if not impossible for President Biden to use agency action to implement this climate agenda. Biden’s EPA is expected to introduce new rules to address power plant emissions in early 2023 and hopes to finalize these regulations in 2024. The Court’s decision limits what the EPA can do and if the EPA exceeds these limits, the new regulations will be challenged in the courts. To make matters worse for the President’s agenda, on July 14th, Senator Manchin announced that he would not support any climate or clean energy programs, effectively killing the $550 billion portion of the Build Back Better Act that supported a wide range of efforts to combat global warming.

Executive Action To Address Climate Change

With few other options, President Biden may try to use his executive powers to address climate change. So far, the President has stopped short of declaring a climate emergency. However, he has started to take some executive actions. An ongoing investigation by the Department of Commerce has caused an almost total halt to the importation of solar panels. As a result of the Commerce investigation, developers who imported panels from Asia were at risk of incurring significant penalties. The investigation, initiated by a domestic panel manufacturer (Auxin Solar), alleges that Chinese-made panels are being shipped to the US from Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and Cambodia to avoid duties on solar modules. To address this shortage, President Biden declared a national emergency “with respect to the threats to the availability of sufficient electricity generation capacity to meet expected customer demand.” This emergency gave the President authority to permit the importation of solar panels from Southeast Asia for 24 months without risk of tariffs.

The legislative basis for Biden’s action was Section 318(a) of the Tariff Act of 1930[4], a provision that historically was only used in wartime or times of nationwide need. For example, Harry Truman used this provision to allow duty-free important of lumber needed for construction to help alleviate a housing shortage faced by veterans returning from WWII. In citing this authority, Biden’s declaration focuses on the need for additional solar capacity stating that the “acute shortage of solar modules and module components has abruptly put at risk near-term solar capacity additions that could otherwise have the potential to help ensure the sufficiency of electricity generation to meet customer demand.”[5]

The executive action was well received by solar developers, but the action is not without legal risk. The party that brought the anti-circumvention claim may challenge Biden’s authority to use his executive power in this way. We do not know if Auxin will challenge the President’s executive action in court, arguing that the President exceeded his authority under Section 318(a). As of the date of this letter, no such legal challenge has been filed. The Commerce Department is expected to issue a preliminary finding on Auxin’s claim in August.

On the same day that Biden used executive powers to address the solar tariff issue, he issued five Presidential memoranda setting out the basis for using the Defense Production Act (Section 303) to promote domestic production of solar equipment. The memoranda stated that the domestic production of such parts was essential to the US national defense. These findings allow the President to purchase items for the US Government’s use and to develop domestic production capabilities. It is still unclear what steps will be taken in accordance with Section 303. The White House press release simply stated that the White House and the Department of Energy “will convene relevant industry, labor, environmental justice, and other key stakeholders as we maximize the impact of the DPA tools made available by President Biden’s actions.”

The President’s authority to use Section 318(a) of the Tariff Act or the Defense Production Act to support climate initiatives was not reviewed by the Supreme Court in West Virginia v. EPA, however, we expect that if these issues come before the Court, the Court is likely to also question the basis for using Executive action to address climate change.

In the Near Term: Energy Policy Remains A State Issue

The Supreme Court’s decision and its “major question” logic almost ensures that all energy-related decisions will be made at the state level. As in prior quarters, some states continue to take a leadership position on climate change, while others do not consider it an important issue. California is currently considering legislation that requires broad climate disclosure. California Senate Bill 260, the Climate Corporate Accountability Act, will require all US-based companies with revenues in excess of 1 billion dollars that are doing business in California to report on Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 emissions. The bill goes further than the SEC’s reporting regulations, covering both private and public companies and mandating that all reporting companies disclose Scope 3 emissions – regardless of materiality. In addition, the bill includes significant penalties - $25k per day for 30 days for late filing increasing to $50k per day after that and a civil penalty of $1M per violation for repeatedly or intentionally violating the new rules.

In July, broad climate change legislation in Massachusetts passed both Houses and it now sits on the Governor’s desk. This legislation would facilitate additional onsite solar, expand the installation of energy storage, explore needed transmission investments, ban the sale of gasoline and diesel vehicles by 2035, add more EV chargers, allow up to 10 municipalities to ban fossil fuel connections, and increase emission reporting for buildings over 20,000 sq. ft. Our clients in New York State and New York City are also facing extensive climate rules driven by New York’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act and New York City’s Local Law 97, among other regulations.

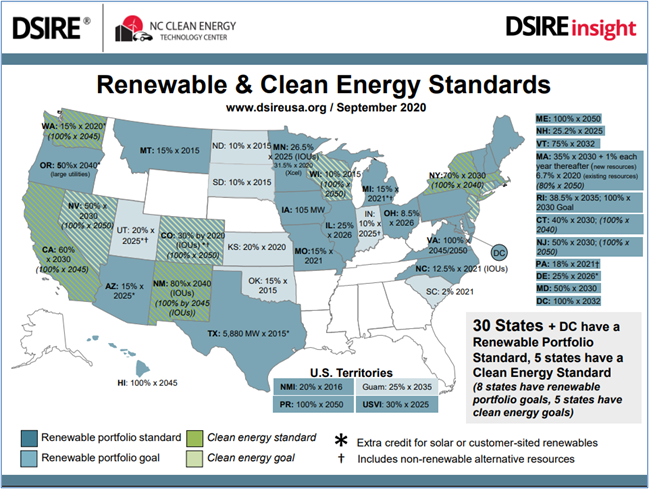

Without clear federal legislation or regulation, energy policy remains a patchwork quilt. Almost every state has a different approach. For example, 24 states plus DC have adopted greenhouse gas emissions targets. The map in Figure 2 gives a sense of the markedly different policies.

Figure 2: Renewable & Clean Energy Standards from dsireusa.org

Conclusion

The energy transition remains in the control of states, utility commissions, and regional transmission organizations. For good or bad, our clients need to look at each state’s rules to understand the risk and opportunities posed by the energy transition. In response, the team at 5 continues to expand its state regulatory and sustainability team so we are positioned to help our clients manage the issues on a state-by-state basis. As always, please do not hesitate to contact me or other members of the 5 team if you have energy-related questions or you would like to discuss the issues covered in this letter in more detail.

Download the PDF version here.

[1]The Clean Air Act was first signed into law by President Nixon in December 1960. In 1990, the Clean Air Act was revised and expanded with bipartisan support and signed into law by President George H.W. Bush.

[2]“Precedent teaches that there are “extraordinary cases” in which the “history and the breadth of the authority that [the agency] has asserted,” and the “economic and political significance” of that assertion, provide a “reason to hesitate before concluding that Congress” meant to confer such authority.” Roberts’ opinion.

[3]Scope 1 are direct emissions, Scope 2 are emissions from purchased energy and Scope 3 are emissions from upstream or downstream activities.

[4]This empowers the President, after declaring a state of emergency, to ”extend during the continuance of such emergency the time herein prescribed for the performance of any act, and may authorize the Secretary of the Treasury to permit, under such regulations as the Secretary of the Treasury may prescribe, the importation free of duty of food, clothing, and medical, surgical, and other supplies for use in emergency relief work.”

[5]Biden Declaration of Emergency June 6, 2022 Statement.